Doing Better Than Grading on a Curve

As educators, we should promote the best outcomes for our students in the areas of information retention, knowledge application, and the grades that come with them. In some respects, grading on a curve rewards students when a test’s outcomes are below the average expected result.

There are surely positives to grading on a curve; otherwise, educators wouldn’t do so. Some positives come to mind immediately—grading on a curve allows educators to challenge their students with difficult exams without disrupting their final grades.

But is grading on a curve equitable to all students? Is that approach best for the learning outcomes of a learner? There are failures of grading on a curve and ways in which educators can avoid doing so.

Who Grades on a Curve and Why?

Grading on a curve can be quite controversial in academia. There are students and teachers alike who are in favor of curved grading and those who are staunchly opposed. But which educators are grading on a curve, and why do they choose to do so?

According to The Impact of Grading on the Curve: A Simulation Analysis by Professor George Kulic and Professor Ronald Wright of Le Moyne College, grading on the curve is common in higher education and is especially popular in science classes.

Advocates for grading on a curve cite many supposed issues as a reason why the curve should be introduced to their grading. Some of these issues include class size, class difficulty, exam difficulty, prior exam averages, and the necessity of having a set grade distribution. Those that grade on a curve either agree with these issues and think that they necessitate adjusting grades or do so as a result of educational guidelines put in place.

Though many professors currently use grading on a curve to adjust their student’s scores either on examinations or for their final grades, this system has agreed-upon failures.

The Failures of Grading on a Curve

Grade inflation is one of the negative outcomes of grading on a curve. Hamilton College’s Professor S.A. Miller wrote in a web essay titled What Does It Mean to Curve Grades? that “grade inflation lowers standards, discounts achievement, and hurts students in the outside world more than students realize.”

In another way, tactics against grade inflation also harm students. Kulic and Wright discuss a particular Psychology Department that recommended final grade distributions of “15% A’s, 25% B’s, 45% C’s, 10% D’s, and 5% F’s.” By dictating that a class can only receive a certain distribution of grades by grade letter, professors are encouraged to ignore that they may have received a group of students that exists as a statistical outlier. A professor with an exceptional class could be encouraged to alter grades against the high marks their students are receiving. The opposite is also true.

Curves can also fail to highlight detriments in an instructor's teaching, lessons, and class modules. An acceptance that the average score for a given class is far below average is an indicator that the course is not sufficiently teaching materials to its students. After all, the primary goal of education is just that—education. This methodology emphasizes the letter grade instead of the knowledge received from the course.

With an emphasis on the letter grade, there is also a misunderstanding of how some students learn. Professor Devin Camenares of Alma College wrote about the effect of difficult exams and curved grades and how repeated poor performance impacts students in Better Remedies For Bad Exams. In it, he discussed how overly difficult or arduous exams are burdensome rather than enlightening and do not serve students in their education.

Alternatives to Grading on a Curve

With the failures of grading on a curve in mind, the alternatives seem obvious. Simply not grading on a curve seems like a reasonable solution, but failing to apply a curve puts more students at risk of failing in overly hard or difficult courses. The question then is should they fail, or should education adjust?

The curve is simply a symptom of a larger problem. Consideration of testing practices and how knowledge is tested is called into question by acknowledging the shortcomings of grading on a curve. If exam results consistently have averages, are the exams too hard, or is the material not taught in a way that is being absorbed by the students? Is the course moving too fast? Is the instructor engaging enough? Are the students qualified to be taking the course? Many factors could be at play when looking at average exam scores.

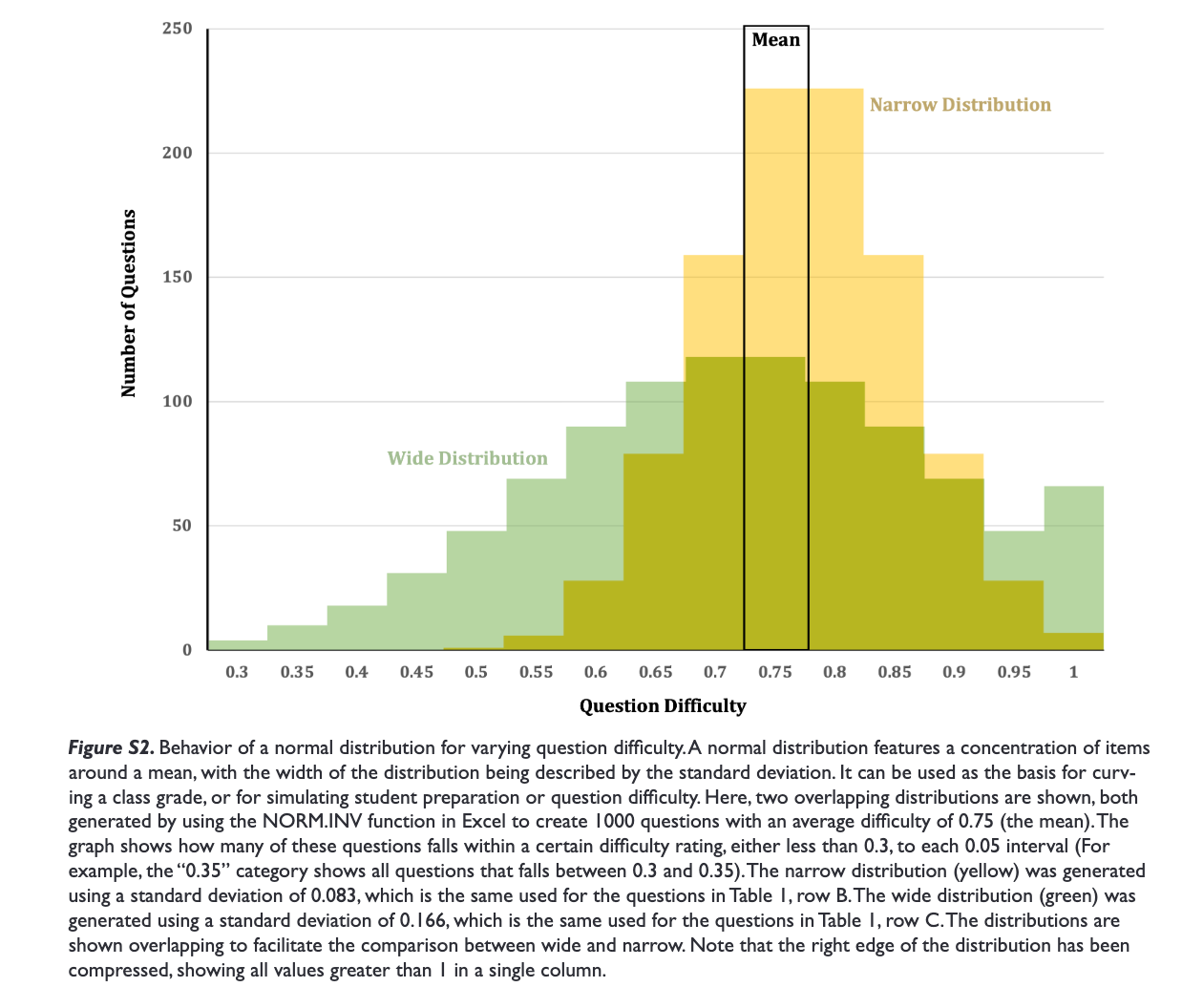

In a way, it may be that grading on a curve is an easier solution because there are so many factors that lead to low average exam scores. Other possibilities exist, though, including varying the level of difficulty in exams. Professor George Kulic and Professor Ronald Wright also explored this possibility in a simulation in The Impact of Grading on the Curve: A Simulation Analysis, finding that exams made up of fewer amounts of easy and hard questions but with more moderate questions more normally distributed the average.

Similarly, the suggested findings of Professor Devin Camenares in Better Remedies For Bad Exams were that eliminating the hyper-competitive environment of academia could provide better results. He suggested that faculty ratings are poorer from students who receive poor grades, which incentivizes faculty to curve grades to make up for the deficit. However, improving the testing methods would eliminate these considerations in theory.

Conclusion

All in all, eliminating low class averages is the best alternative to grading on a curve. These low class averages are unfair to learners when the grades are curved and when they are not, as they indicate information that is either not being retained or testing methods that are too difficult or stressful for the students to rise to the occasion for.

While making changes to exams may not be easy and will come with trial and error, improving how exams are handled in higher education will have positive outcomes for students and educators.